An Integration Competency Center (ICC) or Integration Center of Excellence (COE) is a shared services function consisting of people, technology, policies, best practices, and processes – all focused on rapid and cost-effective deployment of data integration projects critical to meeting organizational objectives.

In the past we centered conversations centrally around ICC’s, but in the rapidly expanding world of data management we need to consider a wider set of COE-based capabilities that are necessary to archive the goals of the business. We also want to continue utilizing Lean concepts to emphasize value creation for end customers, continuous improvement, and eliminating waste as a sustainable data management practice. A COE may be implemented without adopting Lean practices, but the reverse is not generally feasible; Lean disciplines require the structure and focus of a COE in order to achieve the desired results.

Organizations have found that there is a direct connection between the caliber of their COE’s and their ability to respond quickly to changing processes, intense competition, and demanding customers. In short, the set of COE’s that support core data management capabilities are an enabler for the delivery of trustworthy data in real time.

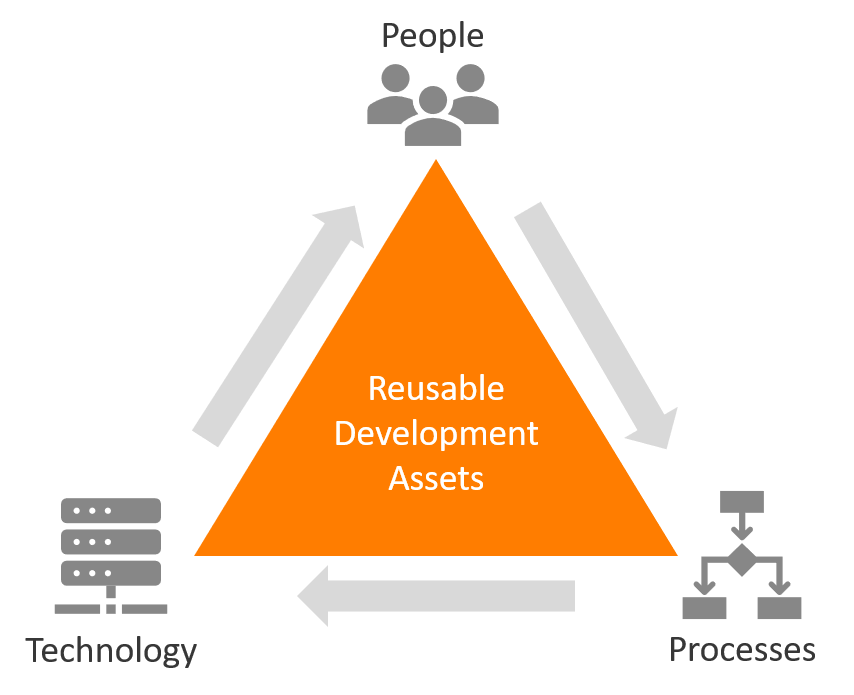

A COE is a strategy that has multiple dimensions that include:

- An organizational structure (federated, centralized, or hybrid) and people with special skills and competencies.

- Defined service offerings supported by processes, best practices and data integration policies.

- Technology, tools, and standards to support the capabilities it offers.

Conceptual Picture of Core COE Dimensions

While any COE may be a temporary unit focused on a specific program, it is generally used to describe a permanent part of an organization that is responsible for maintaining repeatable methods, sustaining data integration services, and providing direction for the movement of information within an organization.

Business Drivers and Objectives

There are many reasons that organizations may wish to establish data management COE’s. The following are just a few:

- To optimize the utilization of scarce resources by combining staff and tools into one group.

- To provide tighter governance and control over a critical aspect of the business or infrastructure.

- To improve the customer experience by integrating information and establishing consistent processes across channels and products.

- To reduce project delivery times as well as development and maintenance costs.

- To improve Return on Investment (ROI) through re-use of low-level building blocks, application components and codified business rules.

- To decrease duplication of data integration and data quality efforts and to promote the concept of re-use within projects and the enterprise.

- To build on past successes instead of reinventing the wheel with each project.

- To lower total technology cost of ownership by leveraging technology investments across multiple projects.

- To capture best practices and lessons learned from one project to the next and build a knowledgebase to secure the above objectives.

In short, a COE is anything that has a perceived value if two or more functional groups need to collaborate and to sustain that collaboration across multiple projects or over a long time period. The business value of capturing lessons learned through experience and knowledge management of common patterns and procedures in order to achieve true integration of data brings value to the organization.

Maturity Levels

Another way to look at data management is to examine how data management technologies and management practices have evolved and matured over the past 50 years. The figure below summarizes four stages of evolution that have contributed to increasingly higher levels of operational efficiency. Hand coding was the only technology available until around 1990 and is still a common practice today, but it is gradually being replaced by modern methods. The movement to standard tools, more commonly known as middleware, began in the 1990s, followed by industry consolidation of tool vendors during the first decade of the 2000s, resulting in more “suites” of tools that provide the foundation for an enterprise integration platform. And now many organizations are moving to cloud-first strategies, offloading the risk of the tools and environments to third parties and enabling rapid delivery of new capabilities and functions while increasing the ability to use more data than ever before.

As we look to the future, we see the emergence of the data management factory as the next wave of integration technology in combination with formal management disciplines. This wave stems from the realization that of the thousands of integration points that are created in an enterprise, the vast majority are incredibly similar to each other in terms of their structure and processing approach. In effect, most data management logic falls into one of a couple of dozen different “patterns” or “templates”, where the exact data being moved and transformed may be different, but the general flow and error-handling approach is the same. But with new methods to understand all the data being brought on, being able to master it to create quality and to address privacy and other regulatory needs is a must for all data management strategies -- and the COE is in place to support that. The COE can establish a high degree of automation to the process of building and sustaining integration points.

Management practices have also evolved from ad hoc or point-in-time projects to broad-based programs (projects of projects), to COE’s and now to Lean techniques. A major paradigm shift began early in the current century around the view of integration as a sustaining practice. The first wave of sustainable management practices is encapsulated by the ICC. It focused primarily on standardizing projects, tools, processes, and technology across the enterprise and on addressing organizational issues related to shared services and staff competencies. The second wave of sustainable practices is the application of Lean principles and techniques to eliminate waste, optimize the entire value chain, and continuously improve. The management practice that optimizes the benefits of the Integration Factory is Lean Integration. The combination of factory technologies and lean practices results in significant and sustainable business benefits.

The timeline shown at the bottom of the evolution graphic represents the period when the technology and management practices achieved broad-based acceptance. There is no date on the first evolutionary state since it has been with us since the beginning of the computer software era. The earlier stages of evolution don’t die off with the introduction of a new level of maturity. In fact, there are times when hand coding for ad hoc integration needs still makes sense today. That said, each stage of evolution borrows lessons from prior stages to improve its efficacy.

These four stages of evolutionary maturity are as follows:

- Project: disciplines that optimize integration solutions around time and scope boundaries related to a single initiative.

- Program: disciplines that optimize integration of specific cross-functional business collaborations, usually through a related collection of projects.

- Sustaining: disciplines that optimize information access and controls at the enterprise level and view integration as an ongoing activity independent of projects including a COE.

- Lean: disciplines that optimize the entire information delivery value chain through continuous improvement driven by all participants in the process

COE Implementation Approach

Implementing a COE involves multiple aspects of organization, people, process, technology, and policy dimensions. The implementation of a COE may be very rapid in organizations that have the motivation and resources to achieve full results quickly; while other organizations may ‘grow’ a full function COE over time. In either case, a key to success is to begin with a solid plan and execute it with the long-term COE objective in mind.

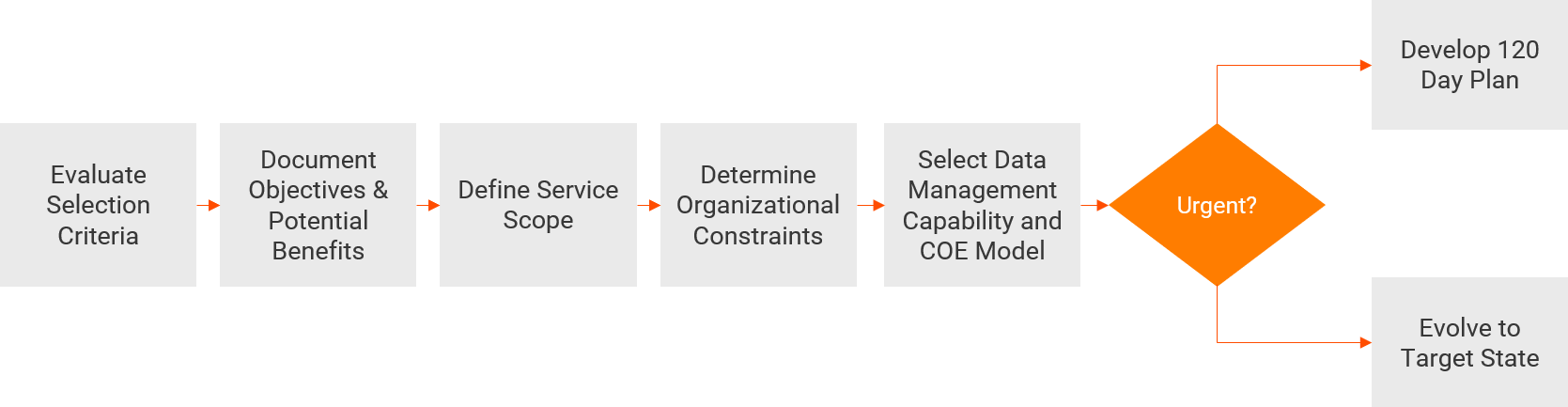

A high-level approach to selecting the appropriate COE model and developing an implementation approach is shown in the figure below:

Because each type of COE has its own advantages, organizations considering implementing any COE should begin by defining the company’s data management goals and the processes needed to accomplish them. Setting the goals and processes clarifies which type of COE would be most appropriate, and which roles and technologies it requires.

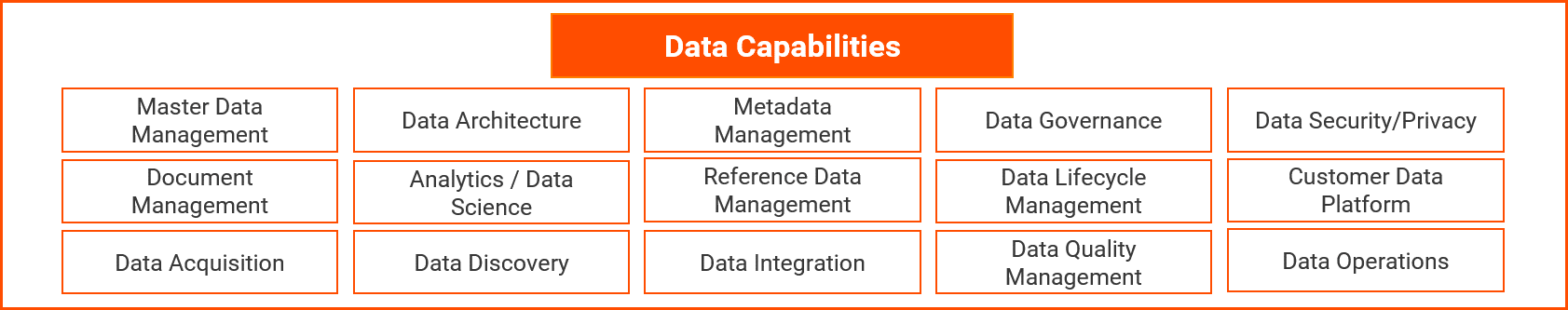

It is important that when setting up the COE and aligning it to the business objectives the utilization of the Data Strategy Framework will be critical. The framework is used to outline the overall strategy to support data management and through that the Critical Data Capabilities (see below) that are needed. It is around these data capabilities that COE’s should be established.

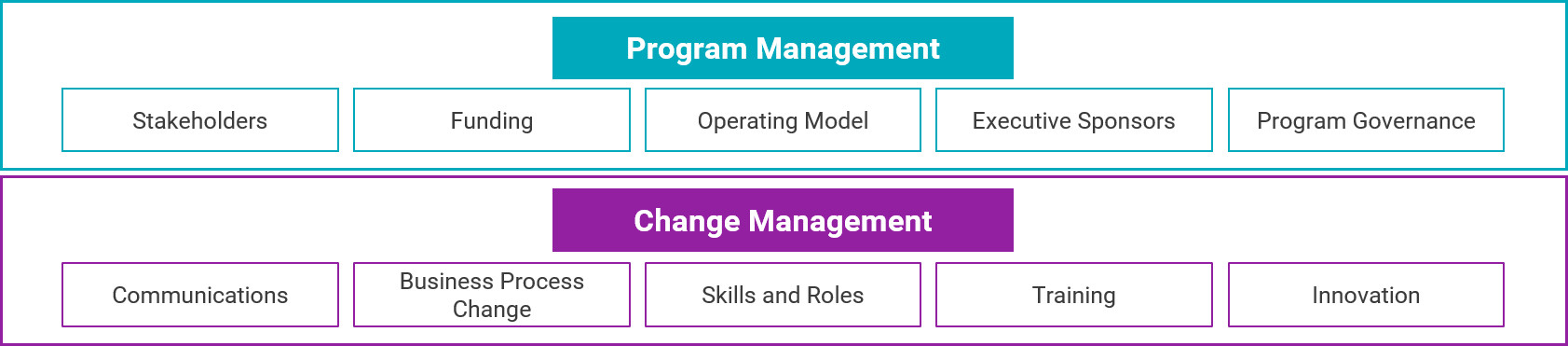

The challenge when starting from scratch, however, is similar to the proverbial “chicken and egg” problem. Should you develop the strategy first and then bring the resources on board, or should you first establish the core leadership team and let them develop the strategy? The answer is both. Development of the strategy should involve an iterative process with the executive sponsor driving a top down process and the COE team members (once they are in place) building the bottom-up plan. The critical part of the creation of the COE is to consider the other building blocks that are outlined in the Data Strategy that outline the Program Management and Change Management efforts. These will align back to the data capabilities and be in support of the overall COE’s goals.

It’s also possible that the COE may be developed spontaneously as a grass roots movement and grow organically. Only in hindsight does the organization recognize the COE for what it is. In this scenario, the COE team members may in fact be the ones best suited to documenting the strategy and gaining formal management agreement.

The recommended approach that has seen the most success starts with a top-down strategy led by an executive sponsor. The executive sponsor begins with the presumption that data management capabilities are an enabler of the business strategy and that having a permanent part of the organization focused on the various data management capabilities as a discipline is a critical success factor.

In summary, implementing a COE is a seven-step process:

- Evaluate Selection Criteria: Determine the recommended model based on best practice guidelines related to organizational size, strategic alignment, business value, and the urgency to realize significant benefits.

- Document Objective and Potential Benefits: Define the business intent or purpose for the COE and what the desired or expected benefits are (this is not a business case at this stage).

- Define Service Scope: Define the scope of services that will be offered by the COE (detailed service definitions occur in step 6 or 7).

- Determine Organizational Constraints: Identify budget limitations or operational constraints imposed by factors such as the geographic distribution of operations and the degree of independence of operational groups.

- Select a COE Model: Recommend a model and gain executive support or sponsorship to proceed. If there is an urgent need to implement the COE, move to step 6 – otherwise proceed to step 7.

- Develop a 120 Day Implementation Plan: Leverage the COE Best Practice for implementing and launching a COE.

- Evolve to Target State: Develop a future-state vision and begin implementing it.

Of course, it’s not as simple at the seven-step process may indicate. The strategy needs to be reviewed and refreshed on a regular basis and there are a number of other elements which may be just as critical, including:

- Architecture Principles

- Outsourcing Strategy

- Financial Policies

- Business Alignment

- Supplier Partnerships

- Standards Selection

The COE Organization Model and the people, process, and technology considerations are the base. Detailed activities include considerations for selecting the right organizational model, assembling and training staff, defining services and selecting technologies and other dimensions.

Each COE Competency is a component that can be used individually or in combination with other competencies, as required by the defined scope and structure for a given COE. For example, while Financial Management is not an essential competency for a Best Practices COE, it is essential for the Shared Services and Central Service COE models.

The COE competencies for each discipline are designed to extend or leverage the existing body-of-knowledge and provide information on how to apply that knowledge in a COE context. For example, COE Competencies and Best Practices for Financial Management won’t make you a finance expert, but they will help you to work more effectively with the finance department in planning and managing the financial aspects of a COE and to use chargeback methods to create appropriate organizational behavior.

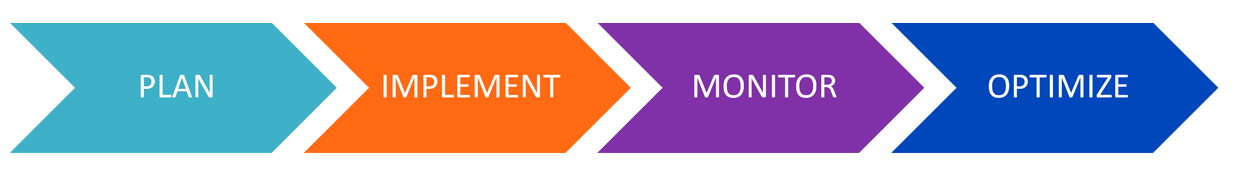

Lean Implementation Approach

Lean and COE’s are complementary. The COE best practices address the core organizational, people, process, technology and policy activities associated with establishing and operating a successful shared service function. Lean builds on the COE core practices by adding a management system for continuous improvement and factory automation. More specifically, Lean is the systematic use of seven principles in the ongoing operations of a COE:

- Focus on the customer and eliminate waste: Maintain a spotlight on customer value and use customer input as the primary driver for the development of services and integration solutions. Waste elimination is related to this principle, since waste consists of activities that don’t add value from the customer’s perspective rather than from the supplier’s perspective. Related concepts include optimizing the entire value stream in the interest of things that customers care about and just-in-time delivery to meet customer demands.

- Continuously improve: Use a data-driven cycle of hypothesis-validation-implementation to drive innovation and continuously improve the end-to-end process. Related concepts include amplifying learning, institutionalizing lessons learned, and sustaining integration knowledge.

- Empower the team: Share commitments across individuals and multifunctional teams and provide the support they need to innovate and try new ideas without fear of failure. Empowered teams and individuals have a clear picture of their role in the value chain, know exactly who their customers and suppliers are and have the information necessary to make day-by-day and even minute-by-minute adjustments.

- Optimize the whole: Make trade-offs on individual steps or activities in the interest of maximizing customer value and bottom-line results for the enterprise. Optimizing the whole requires a big-picture perspective of the end-to-end process and how the customer and enterprise value can be maximized even if it requires sub-optimizing individual steps or activities.

- Plan for change: Apply mass customization techniques to reduce the cost and time in both the build and run stages of the integration life cycle. The development stage is optimized by focusing on reusable and parameter-driven integration elements to rapidly build new solutions. The operations stage is optimized by leveraging automated tools and structured processes to efficiently monitor, control, tune, upgrade, and fix the operational integration systems.

- Automate processes: Judiciously use investments to automate common manual tasks and provide an integrated service delivery experience to customers. In mature environments this leads to the elimination of scale factors, the ability to respond to large integration projects as rapidly and cost-effectively as small changes, and the removal of integration dependencies from the critical implementation path.

- Build quality in: Emphasize process excellence and build quality in, rather than trying to inspect it in. Related concepts include error-proofing the process and reducing recovery time and costs.

From an overall implementation strategy, there are two fundamental implementation styles for Lean; top down and bottom up. The top-down style starts with an explicit strategy with clearly defined (and measurable) outcomes and is led by top-level executives. The bottom-up style, which is sometimes referred as a “grass roots” movement, is primarily driven by front-line staff or managers with leadership qualities. The top-down approach generally delivers results more quickly, but may be more disruptive. You can think of these styles as revolutionary versus evolutionary. Both are viable.

While Lean is relevant to all large organizations that use information to run their business, there are several prerequisites for a successful Lean journey. The following five questions provide a checklist to see if Lean Integration is appropriate for a given organization and which style may be most appropriate:

Is there senior executive support for improving how integration problems are solved for the business?

Support from a senior executive in the organization is necessary for getting change started and critical for sustaining continuous improvement initiatives. Ideally the support should come from more than one executive, at a senior level such as the CXO, and it should be “active” support. You want the senior executives to be leading the effort by example, pulling the desired behaviors and patterns of thought from the rest of the organization.

It may be sufficient if the support is from only one executive, and if that person is one level down from C-level, but it gets harder and harder to drive the investments and necessary changes as you water down the top-level support. The level of executive support should be as big as the opportunity. Even with a bottom-up implementation style, you need some level of executive support or awareness. At some point, if you don’t have the support, you are simply not ready to formally tackle a Lean Integration strategy.

Is there a committed practice leader?

The second prerequisite is a committed practice leader. By “committed” we don’t mean that the leader needs to be an expert in all the principles and competencies on day one, but the person does need to have the capability to become an expert and should be determined to do so through sustained personal effort. Furthermore, it is ideal if this individual is somewhat entrepreneurial, has a thick skin, is customer-oriented, and has the characteristics of a change agent.

If you don’t have top leadership support or a committed practice leader, there is little chance of success. This is not to suggest that a grassroots movement isn’t a viable way to get the ball rolling, but at some point the bottom-up movement needs to build support from the top in order to institutionalize the changes that will be necessary to sustain the shift from siloed operations to integrated value chains.

Is the “Lean director” an effective change agent?

Having a Lean director who is an effective change agent is slightly different from having one who is “committed.” The Lean champion for an organization may indeed have all the right motivations and intentions, but simply have the wrong talents. For example, an integrator needs to be able to check his or her ego at the door when going into a meeting to facilitate a resolution between individuals who have their own egos. Furthermore, a Lean perspective requires one to think outside the box—in fact, to not even see a box and to think of his or her responsibilities in the broadest possible terms.

Is the corporate culture receptive to cross-organizational collaboration and cooperation?

Many (maybe even most) organizations have entrenched views of independent functional groups, which is not a showstopper for a Lean program. But if the culture is one where independence is seen as the source of the organization’s success and creativity, and variation is a core element of its strategy, a Lean approach will likely be a futile effort since Lean requires cooperation and collaboration across functional lines. A corporate culture of autonomous functional groups with a strong emphasis on innovation and variation typically has problems implementing Lean thinking.

Can the organization take a longer-term view of the business?

A Lean strategy is a long-term strategy. This is not to say that a Lean program can’t deliver benefits quickly in the short term—it certainly can. But Lean is ultimately about long-term sustainable practices. Some decisions and investments that will be required need to be made with a long-term payback in mind. If the organization is strictly focused on surviving quarter by quarter and does little or no planning beyond the current fiscal year, a Lean program won’t achieve its potential.

If you are in an organizational environment where you answered no to one or more of these questions, and you feel compelled to implement a Lean program, you could try to start a grassroots movement and continue lobbying senior leadership until you find a strong champion. There are indeed some organizational contexts in which starting a Lean program is the equivalent of banging your head against the wall.

Lean requires a holistic implementation strategy or vision, but it can be implemented in incremental steps. In fact, it is virtually impossible to implement it all at once, unless for some reason the CEO decides to assign an entire team with a big budget to fast-track the implementation. The idea is to make Lean Integration a long-term sustainable process. “Long-term” is about 10 to 20 years, not just the next few years. When you take a long-term view, your approach changes. It certainly is necessary to have a long-term vision and plan, but it is absolutely acceptable, and in many respects necessary, to implement it incrementally in order to enable organizational learning. In the same way, an ICC can start with a small team and a narrow scope and grow it over time to a broad-based Lean Integration practice through excellent execution and positive business results.

The Data Management Factory

The Data Management Factory (DM Factory) is a core concept in a holistic set of COEs that support Data Management and have adopted Lean principles. The factory is a cohesive DM technology platform that automates the flow of materials and information in the process of building and sustaining integration points. More specifically, the DM Factory is the collection of Informatica products that that should be considered for certain ongoing DM needs. For example, an enterprise that has an ongoing need (beyond just one project) for application migration or consolidation in support of its M&A activities or application portfolio rationalization strategy, could implement an application migration factory using a collection of products like:

- Cloud Services

- PowerCenter

- PowerExchange

- Enterprise Data Catalog

- Data Quality

- Axon

Conversely, if the focus of the COE is on B2B operations, rapid on-boarding of external customers or suppliers and ongoing partner management, then a B2B Integration Factory could be implemented based on products such as:

- Cloud Services

- PowerCenter

- PowerExchange

- Enterprise Data Catalog

- Process Organization

- Data Acquisition

- Managed File Transfer

- Data Quality

- Axon